By Michael Mozdy

Utah is known for plenty of excellent things. The financial responsibility of our state government, the incredible business climate for entrepreneurs, the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, and the greatest snow on earth are just a few of the notable ones. It might surprise you to learn, however, that we’re far below the national average on one important health metric: breast cancer screening.

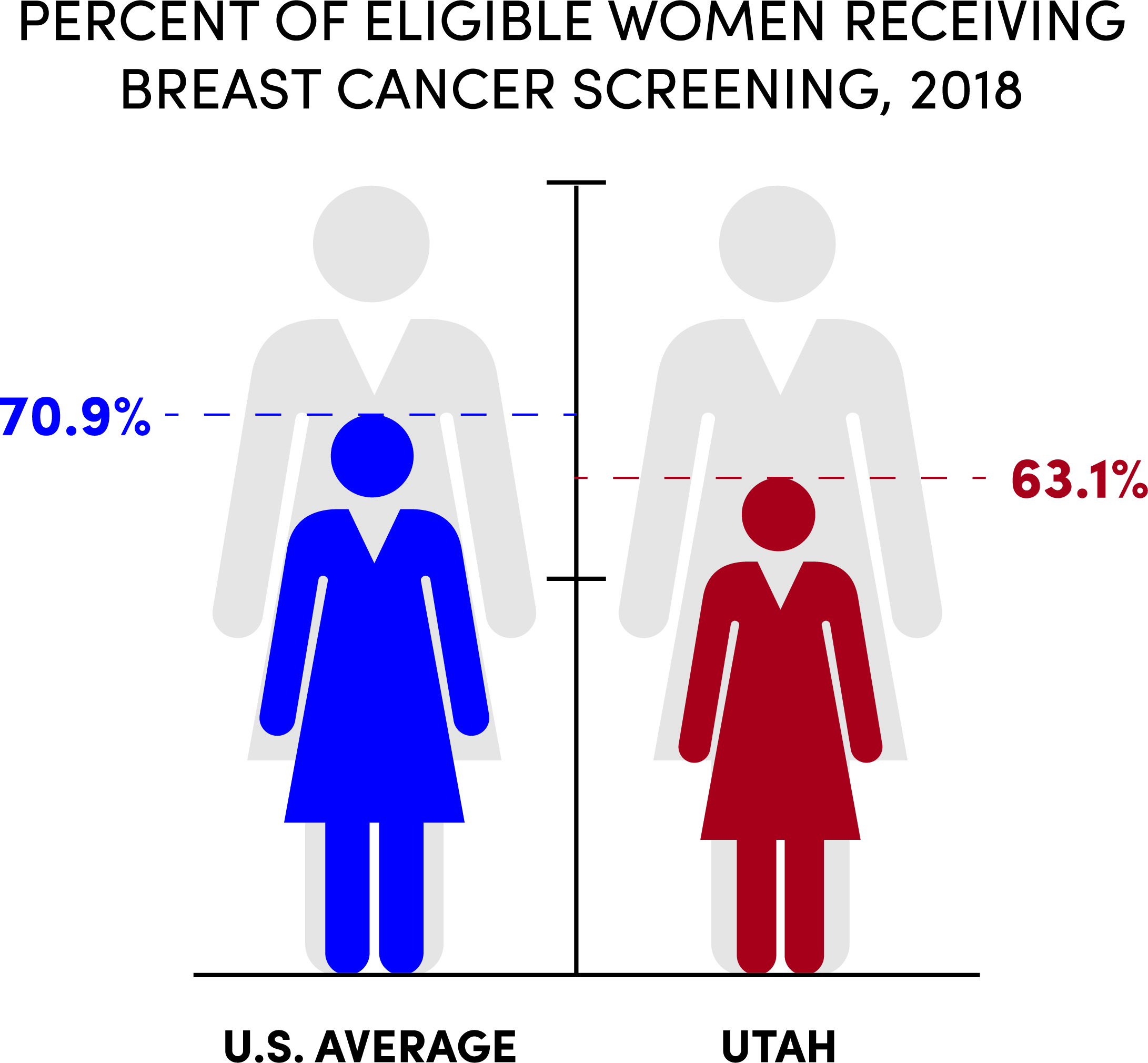

The data from a 2018 study tell the tale. Nationwide, 70.9% of women age 40 or older reported having a breast cancer screening exam sometime in the past two years. In Utah, only 63.1% of women reported the same. We’re so far behind, that the Utah Department of Health reports that our statewide goal is 76% while the nationwide average goal is 81.1%.

The data from a 2018 study tell the tale. Nationwide, 70.9% of women age 40 or older reported having a breast cancer screening exam sometime in the past two years. In Utah, only 63.1% of women reported the same. We’re so far behind, that the Utah Department of Health reports that our statewide goal is 76% while the nationwide average goal is 81.1%.

Why does this matter? Simply put, early cancer detection saves lives. Breast cancer is the #1 cause of cancer-related death for women in Utah, and when cancer is detected earlier, survival rates are much greater. That’s why doctors recommend that women 40 and older receive regular breast screenings (mammograms).

The Utah Department of Health examined the data closely and determined that three factors had a significant impact on women getting a mammogram on the recommended schedule: age, household income, and educational level. Women between 40-50, women in households making less than $25,000 annually, and women with less than a college degree all had significantly lower rates of screening. Neither race nor geographic location within the state had a significant impact.

Thus, some women are not able financially and some are not sufficiently motivated to make a mammography visit. For health care providers who want more women to get breast screenings, it’s logical to try to bring the mammogram to them if they can’t or won’t come to the mammogram.

Thanks to the long-range vision of Ben Tanner, MHA, executive director of HCI’s cancer hospital, that’s exactly what we’re doing.

A Bus Above the Rest

Tanner has been thinking about mobile cancer screening for a decade and even wrote his Master’s thesis on the topic. A screening bus that travels throughout Utah would embody Tanner’s mantra that Huntsman Cancer Institute’s cancer hospital can provide “cancer care without walls,” and his vision included their characteristic high level of patient-centeredness.

“The planning team spent a year investigating other programs around the country, seeing what worked and didn’t, what types of vans and buses were available, and how the staffing, electrical and IT needs might be work,” explains Phoebe Freer, MD, the section chief for Breast Imaging in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences. Armed with a horde of best practices and several sources of funding, they picked out a massive, 45-foot-long RV and outfitted it with the best equipment and nicest furnishings they could dream up.

“It’s probably the nicest mammography suite we have in our system,” admits Freer. She and the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences advised the HCI team on state-of-the-art 3D mammography equipment. The bus also contains a private dressing room, an exam room where skin cancer screenings or biopsies could be done in the future, a waiting room, and furnishings that put people at ease and help them feel well cared for.

Interior of the Cancer Screening and Education Bus the state-of-the-art 3D mammography equipment.

More Complex than a Bloodmobile

Unlike a bloodmobile that can pull up to most businesses and parking lots to collect donations, breast cancer screening requires careful coordination with a patient’s primary care provider. A woman must have a provider’s order for a mammogram and our radiologists need to view prior mammograms to best interpret any changes that may have occurred in a patient’s breast tissue. And then there’s the question of follow up: what happens if a biopsy or another scan is needed, and how is the patient’s insurance carrier involved in these interactions? Our team carefully orchestrates where the bus goes and how they coordinate with primary care physicians to make this process easy for patients.

The Cancer Screening and Education Bus first hit the road in September of 2019, and 300 women were screened in the first two months, far exceeding their initial goal. Four people enable the day-to-day operations:

- Rebecca Miner, the Patient Relations Specialist who greets patients, registers them, coordinates with their primary care physician for orders and past records, provides screening education and answers any questions they might have.

- Kay Neumann, the Mammography Technologist who performs the scans and works with patients in all aspects of the clinical exam.

- Kaipo Dabin, the driver, who carefully drives the giant rig, parks it in the appropriate places, and takes care of all the automotive needs.

- Lynette Phillips, MPA, the Manager of HCI’s Mobile Screening Program, who schedules the day-to-day operations, works with their community partners, coordinates with the IT staff and radiology faculty, and analyzes the progress of the mobile screening activities.

Each of these team members fills a critical role, enabling the Cancer Screening and Education Bus to visit the right places where as many women as possible can take advantage of the convenience and the excellently coordinated care.

Team members (left-to-right): Shelley Conkey, Mammography Manager; Rebecca Miner, Patient Relations Specialist; Lynette Phillips, Mobile Screening Program Manager; Phoebe Freer, MD, Section Chief for Breast Imaging; and Kaipo Dabin, driver. Not pictured: Kay Neumann, Mammography Technologist.

A Busy Breast Section

Freer, as Section Chief of Breast Imaging in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, is proud of her team of radiologist physicians. “We are gaining national recognition for our excellence in all three areas of our mission: our clinical care, our educational work, and our research,” she says. Indeed, two of our physicians are Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) Fellows – Freer herself and Laurie Fajardo, MD – a distinction reserved for those at the top of the field. With only 128 physicians designated as SBI Fellows out of the 3400 members, having two of them at University of Utah Health speaks to the quality of our faculty. These fellows are well-published, meaning that they not only know the latest research, but they are the ones contributing to it. A third faculty member, Eugene Kim, MD, also was awarded the Wendell Scott Award for Outstanding Research by a Fellow in Training, and in his first 6 months at the University of Utah has already landed in the top 10% of physicians for patient satisfaction. The faculty is dedicated to training the next generation of radiologists as well: Nicole Winkler, MD, is the Residency Director for the department in addition to her large clinical workload.

“Perhaps the most amazing thing,” Freer relates, “is that down to the last person, they’re incredibly nice. It’s rare to have an entire group of physicians who get along, support one another, and are dedicated to our mission.”

It’s a good thing, because their workload is only increasing as we open new health centers and send the Cancer Screening and Education bus around Utah for mobile screening. Our radiologists work in several different locations: HCI, the South Jordan Health Center, the Farmington Health Center, and the Sugarhouse Health Center. Each of these locations offers breast cancer screening appointments, and the three health centers offer some results-while-you-wait appointments, which is the standard of care at HCI. What’s more, Freer and the HCI Community Outreach and Engagement team have been traveling to rural areas in Utah and Wyoming, meeting with physicians and patients to offer them access to our experts. “We want all women in our region to have access to the knowledge and interpretive skills in our system,” Freer emphasizes. Physicians in more rural areas are encouraged to call our breast imaging radiologists with questions about difficult-to-read scans; in this way, we are encouraging ad-hoc consultations to help raise the bar on cancer screening and diagnosis throughout the region.

Breast Imaging faculty. (top row, left to right): Cheryl Walczak, MD, Eugene Kim, MD, Helen Mrose, MD. (seated): Matthew Covington, MD, Laurie Fajardo, MD, MBA, Phoebe Freer, MD, Section Chief, Nicole Winkler, MD, Matthew Morgan, MD, MS,.

The workload that comes to them at their workstations is a well-oiled machine. Screening mammograms rise to the top of their work queue as they are imaged so that they can be interpreted quickly. But they are also reviewing diagnostic scans done via ultrasound and MRI to determine the presence, type, and extent of cancer that may be present. In fact, whenever a new patient enters their system, our radiologists will re-read their history of screening mammograms to have the best baseline possible for comparing to their current scans. It’s a dedication to quality medicine that is unmatched.

Thoughtful Partnerships

In order to make a dent in Utah’s breast cancer screening rate, the team knew that they must focus on underserved and vulnerable populations. Reaching homeless women, for instance, or underserved communitites, is particularly difficult because years might pass before they even see a primary care physician.

“It’s critically important that these patients don’t fall through the cracks.” |

Navigating among these vulnerable populations is possible thanks to Lynette Phillips, who worked for the Utah Department of Health for four years as the manager of the Utah Cancer Control Program prior to coming to University of Utah Health. Phillips brought with her the community partnerships and networks that took years to grow within the state to augment HCI’s existing community relationships.

“It’s about finding the best medical home for the patients we are trying to serve,” explains Phillips. “We partner with leaders in specific communities and listen to them about the best ways to reach their target populations.” These community partners include the Urban Indian Center, the 4th Street Clinic, Sacred Circle Healthcare, the National Tongan American Society, and the Utah Pacific Islander Health Coalition, among others.

This focus on a “medical home” makes infinitely more sense than randomly pulling into parking lots and offering mammograms. The team can arrange in advance for women to come out to the bus directly after their visit to their primary care doctor. They can coordinate with the insurance carriers already identified by the community partner and access health records containing prior scans. And perhaps most importantly, they can arrange follow-up care on the spot.

“It’s critically important that these patients don’t fall through the cracks,” emphasizes Phillips.

“It’s critically important that these patients don’t fall through the cracks,” emphasizes Phillips.

“Yes,” agrees Freer, “especially if they need a diagnostic scan or biopsy after a suspicious lump is detected – we can ensure that this is done.”

It’s not easy, for instance, to arrange a diagnostic scan at HCI’s hospital for a woman who has all of her belongings with her and no transportation, but the team has made this happen. More often, it’s a case of getting an appointment set with the woman’s primary care provider for additional follow up.

In the near future, the team hopes the bus can provide biopsies and other preventative health screenings like skin cancer screening and HPV vaccinations. For now, they’re busy keeping up with the demand for mammography.

“The University of Utah Health Stansbury Clinic is a good example,” illustrates Phillips. They have 1,000 women a month with outstanding mammography orders that haven’t been filled. “It’s not that far away, but women often won’t make the time to travel for a screening mammogram. We were overbooked because the women were so excited to have us there.”

Miner, who sees every woman who steps into the bus, echoes this sense of excitement. “We performed a screening for a patient in her 70s and it was her first mammogram ever. She was extremely grateful that we made an effort to go to her community center.”

The Difference is in the Details

Strategic community partnerships are one aspect of what sets apart HCI’s cancer screening and education programs, and the design of the bus’s interior with a full exam room is another. This allows for a number of potential services that could be added in the future, like precision genetic counseling, skin cancer screening, ultrasound exams, and biopsies.

A third differentiator is that our bus is driven all across Utah – a giant geographic area in comparison to other programs. MD Anderson’s mobile screening van in Texas, for example, only travels around 20 miles from the medical center, and never stays out overnight. In order to serve our rural and frontier populations, we travel hundreds of miles and out of necessity stay out for days at a time.

A third differentiator is that our bus is driven all across Utah – a giant geographic area in comparison to other programs. MD Anderson’s mobile screening van in Texas, for example, only travels around 20 miles from the medical center, and never stays out overnight. In order to serve our rural and frontier populations, we travel hundreds of miles and out of necessity stay out for days at a time.

A reliable and conscientious driver is critical, and we have one of the best in Dabin. He’s been driving large vehicles for a long time with the military and tour bus companies. “He is amazing,” reports Phillips. “The bus is huge and very difficult to maneuver, not to mention expensive and high tech. Kaipo deeply cares about it, he scopes out locations before driving the bus there, and he has great customer service skills.”

A final differentiator for our program is that we can potentially provide scan interpretations faster than other mobile mammography programs. As mammography scans come in, our physician faculty in the Breast Imaging section interpret them and send back recommendations for follow-up care. This seemingly simple process is actually quite the technological feat. A single mammography scan is many gigabytes of data. Huge data needs are one thing, but add the fact that the bus is traveling throughout rural Utah and needs to be self-sufficient, not relying on the presence of someone else’s WiFi is another. The ingenious IT solution involves using LTE cellular networks, a combination of 15 SIM cards from different carriers, and combining all of the data through one point-to-point-encrypted pipeline.

Quick data transfer is important to our radiologists, who have a standard of results-while-you-wait when patients receive a mammogram at HCI. “We’re getting the images within 10 minutes, depending on where the bus is parked,” reports Freer. “This allows us to interpret the scans quickly and efficiently within our normal workflow.”

It’s a great example of how the team refuses to compromise the quality of the care they deliver. They know that highly competent, coordinated care that respects a patient’s time and emotional state lifts up a person exactly when they need it. “Some of the most vulnerable patients the bus has reached have had tears in their eyes saying they didn’t think they could get this level of care,” relates Phillips. “Our goal,” she adds, “is that all women receive mammograms, regardless of living conditions, income and background.”